Formation of Medieval Towns

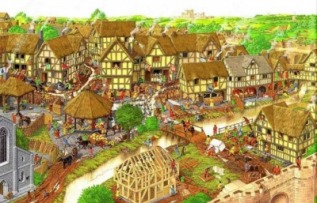

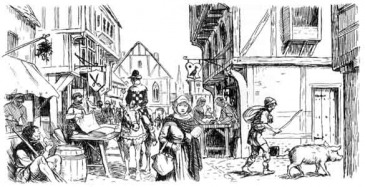

The gatherings of people in Medieval Europe were not large or stable enough to be considered towns until around the 12th century (Rice Jr. 25). From 1086 to 1377 there was an increase in the rural English population alone from around 6% to about 9.25% (Pounds 80). The first towns were mainly in the core of Europe, which besides England included: France, Hungary, Poland, and the Holy Roman Empire (Jordan 181). It was brought about by an economic revolution which produced a bourgeoisie class (also called burghers) that was wealthy enough to be concerned with capitalism (Rice Jr. 25). This class was the first to be offered a wider range of employment than just agriculture, which was the basic requirement of feudal system of the rural areas (Brooke, 118). As well as the bourgeoisie class, the towns were populated with lower nobility, referred to as gentry. (Rice Jr. 25) Below the gentry were the urban town dwellers, and below them the rural peasant class.

Government

From Feudal to Central:

The Importance of the Charter

After the fall of the Roman Empire the European economy reverted back to the barter system (Kenyon 47). By the twelfth century the monetary system was fully functional in most towns (Kenyon 47). Around the same time there was a period of political calm and social stability which stimulated trade (Rice Jr. 36). This created more jobs around the merchant’s permanent storehouses (Rice Jr. 36). Steadily, communities began to expand. Towns began to break ties with their feudal lords who owned the land.

They began to apply for charters, which would declare them communes (Rice Jr. 36). The commune was a “self-governing settlement organization on the base of collective ownership and use of goods and property” (Rice Jr. 36). In return for the freedom of a charter the feudal lord levied taxes on goods, tolls on the roads, and certain goods or services (Rice Jr. 36). With a charter the old feudalist system of government was prevented by a central system of government (Pounds 71).A town’s charter was granted by the feudal authority of the land (Pounds 101). It allowed the town to exist on the feudal lord’s land (Pounds 101), and for self-government, distinct from the countryside (Pounds 101). Until a village gained a charter, it was subject completely to the will of the feudal lord (Pounds 102). Nearly every charter provided for and protected the interests of “commercial activities” (pounds 103). When the laws of the Charters became obsolete, a new, updated charter was written to accurately indicate the government of the time (Pounds 102).

The council and other town authorities

A charter enabled a town to manage its own social and economic matters (Pounds 102). Medieval townfolk were governed in two ways: First as a taxpaying, law-abiding member of the urban community (Pounds 100); and secondly as a member of a gild (Pounds 101). These two roles often overlapped, and so did the governing forces behind them (Pounds 101). A town was governed first by an executive officer who went by any number of names (mayor, provost, Portreeve, etc.), and a city council (Pounds 102). The council guided and advised the executive officer in all decisions (Pounds 102), but it did not always have the people’s best interest at heart. The twenty men who sat on the council were elected by the local upper-class, and whenever a vacancy had to be filled he was nominated by that same upper-class (pounds 102). In this way a few elite families stayed in power (pounds 106), and the rest of the town’s population had little to no effect on the government (pounds 102).

The Economics of a Medieval Town

Gilds

Around the eleventh century early workers unions called gilds arose all over towns in Europe (Kenyon 47). Their main purpose was to regulate the quality and price of all trade within the town. Gilds also helped to protect their workers from the taxes and demands of feudal lords or competition (Kenyon 48). They were opposite the city council in town government and served a different purpose. However because the two groups often controlled by the same people, they usually worked towards similar ends. The urban craftsmen were compelled to join the gild of their trade and share in the management of their craft (Pounds 121). Most gilds were overseen by the rich, upper-class men, but there were a few gilds overseen by women (Kenyon 48). The women’s gilds did the usual women’s work: weaving, brewing, and spinning to name a few (Kenyon 48). There were two different types of gilds: craftsman and merchant (Rice Jr. 52). Both set a standard of workmanship (Rice Jr. 52) within the town aimed at excluding truly shoddy products from the shops and markets (pounds 120). The difference between them was that the merchants gild specialized in buying and selling goods, and the craftsman’s gild were only interested in their particular craft. A member of a gild, a craftsman’s gild in particular, could gain mastership by creating a masterpiece and having the gild “deem it worthy. With a strong central government, this was very helpful; especially when there was economic and political tension from the surrounding feudal territories (Pounds 71).

The 3 Kinds of Urban Trade

1. The Shop

Shops were open for business every day (Pounds 126). They involved basic haggling between a craftsman and a consumer over the price of a good or service (Pounds 126). Generally the shop doubled as a house for the craftsman’s family who either lived behind or above it (Pounds 126).

2. The market

The market was open once a week (Pound 104). It offered more than everyday shopping because the peasants from the countryside would bring goods to sell (Pounds 104). In almost every charter there was provision for an open market one day a week (pounds 126), it was considered a necessary part of town life. Without the market food supplies and the supplies of other goods would run low, leaving the stationary town population with very little to live on.

3. The Fair

The town fair was a very special occasion. It was held once a year (pounds 105) for several days (Pounds 128) because all of the merchants and traders came from such a far distance that trade wasn’t heavy enough to economically support more than just an annual fair (Pounds 128). Goods were brought in by the wagon load, and stalls were set up all through the streets (Pounds 128). Sometimes the narrow town streets would be to small for all of the trade and so the merchants would move out into the open countryside (Pounds 128). Even thought it was a relatively primitive way of handling long-distance trade, the annual fair was a large part of town life .

Daily Life

The expansion of different artesan fields, such as: the cloth industry, miners, metal-workers, shipbuilders, carpenters, and stone masons, also contributed to the merchant trade (Brooke 118). There is really no way to judge today how many different jobs a medieval man might hold over the course of a lifetime (Brooke 119) However, most of the villagers still relied on agriculture for their living (Rice Jr. 33) Their entire lives relied upon a good harvest and a steady garden from spring until fall. Most middle class people lived with enough to survive and a small amount of surplus (depending on the season, and scarcity of food).

A town lived with the ever present fear of two foes: 1) “marauding armies” that would ransack towns and demand or take what they wanted from the villagers, and 2) the unstoppable forces of nature (Pounds 64-65). There were storms, wild animals, and insects to contend with, not to mention the odd thief. Food was especially scarce in the late spring and early summer (Pounds 64). This meant that the price of food went up, and more of the townspeople went hungry. Most of the domesticated animals were used for food, labor purposes, and other extraneous tools or clothing that could be made from their bodies (Pounds 62).

A town lived with the ever present fear of two foes: 1) “marauding armies” that would ransack towns and demand or take what they wanted from the villagers, and 2) the unstoppable forces of nature (Pounds 64-65). There were storms, wild animals, and insects to contend with, not to mention the odd thief. Food was especially scarce in the late spring and early summer (Pounds 64). This meant that the price of food went up, and more of the townspeople went hungry. Most of the domesticated animals were used for food, labor purposes, and other extraneous tools or clothing that could be made from their bodies (Pounds 62).

Rural and Urban Diet

The main peasant diet consisted of wheat, rye, or barley bread; meat and fish; some fruit at certain points in the year; and usually ale to drink (Brooke 90). Most food was seasonal. It had to be stored during the warmer months so that an urban family might survive the harsh winter season (Pounds 64) .Grains had a long shelf-life. They could potentially last the entire winter, however once made into bread or gruel they only lasted a short time. Townsfolk had the same problem with meat. It had to be kept alive and fed until it was to be eaten because the shelf life of slaughtered meat was even shorter than that of bread (Pounds 63). Usually at the beginning of winter there was a gigantic slaughtering of animals In towns all across Europe (Pounds 64). One more uncertainty of town life was guessing when in the winter to slaughter animals. If done too soon or too late, the meat wouldn’t last long enough (Pounds 63). Importation was a necessity because of the rising population of the towns. It just wasn’t possible for the surrounding fields to produce enough to sustain an entire town (Pounds 62). Peasants normally brought in food from the countryside to sell on Market Day (pounds 62).

It was unsafe to consume most of the water found around towns because of the horrendous lack of hygiene, and spread of waste. This meant that ale was the main drink around Europe (Pounds 64). Some of the more wealthy families were able to afford wine on a regular basis, but most of the middle class only drank wine in church for communion (Brooke 100). The countryside peasant and the urban dweller had very similar diets. Urban people were exposed to a slightly wider range of foods because of the merchant trade through the towns (Pounds 63). The only real distinction between the diet of the lower class and that of the upper class was the amount of spices that the wealthy had to hide the rancid taste of their rotten foods (Pounds 63).

It was unsafe to consume most of the water found around towns because of the horrendous lack of hygiene, and spread of waste. This meant that ale was the main drink around Europe (Pounds 64). Some of the more wealthy families were able to afford wine on a regular basis, but most of the middle class only drank wine in church for communion (Brooke 100). The countryside peasant and the urban dweller had very similar diets. Urban people were exposed to a slightly wider range of foods because of the merchant trade through the towns (Pounds 63). The only real distinction between the diet of the lower class and that of the upper class was the amount of spices that the wealthy had to hide the rancid taste of their rotten foods (Pounds 63).

Here are some examples of just a few Medieval Recipes, and links to dozens more:

Haggis:

Soak a sheep’s bladder in salted water for at least twelve hours. Turn the roughened side out, then wash the small bag. Hang the windpipe over the edge of the pot. Cover with water and boil for an hour or two. Afterwards, cut off the pipe and gristle. Finely chop the heart and half of the liver. Add two chopped onions, garlic and oatmeal, and moisten with broth. Put the mixture inside the large bag and sew closed. Boil for approximately three hours, cutting a small hole when the bag begins to swell.

Lampreys in Galytyne:

Skin and gut a lamprey, making sure to keep the blood in another container for later use. Roast the lamprey on a spit and save the grease. Mix ground raisins with rose petals and combine with bread crusts and vinegar, or verjuice. Add powder ginger and the blood and grease to the raisin mixture, then boil together and salt to taste.

Blackmanger:

Cut chicken into chunks, and blend with rice that has been boiled in almond milk and salt and seasoned with sugar. Cook until mixture is very thick and garnish with anise and fried almonds.

Eels:

Skin and gut eels, then cut into chunks and place them in a pan of salted water. Add Chopped parsley, garlic and pepper. Boil until the eel chunks begin to split.

Cheese Crowdie:

Heat soured milk until it separates. Do not boil. Strain the whey. Season the solid Cheese block with salt, pepper and a dab of garlic. Let stand for a day or two.

Check out these links for more Medieval Dishes:

http://recipes.medievalcookery.com/

http://www.godecookery.com/mtrans/mtrans.htm

http://recipes.medievalcookery.com/

http://www.godecookery.com/mtrans/mtrans.htm

Hygiene

cesspit/something similar

The only regular hygiene also resided around the tables of the wealthy. There was usually some kind of hand-washing before meals (Pounds 67). The soap of the peasantry was made from boiling wood ash and animal fat together (Pounds 67). Even when made it was seldom used. A common method for disposing of sanitary waste was a domestic cesspit. This was little more than a hole in the ground covered with wooden boards that had a small hole in the center (Pounds 66). A cesspit was sometimes lined with wickerwork or masonry, but those that weren’t contributed to the ruin of the local water supply (Pounds 66-67). Another method for disposing of waste was simply tossing the contents of a pot out of a window and into a street for a raker to take care of. The raker than raked it into the nearest river, which also helped destroy the local water supply (Pounds 68). Because of the ignorance and disregard about hygiene, any serious illness contracted was likely to be fatal (Pounds 69).

Medicine

The middle ages were rife with disease and death. It waited around the corner; in every meal, in the water. In every step of life there was a danger of becoming ill and never recovering. If one did become ill there was very little that could be done. The pool of medical knowledge was not very deep during medieval times. Little was known about the human anatomy, and this resulted in very high death rates, especially in cities (Pounds 141). Most of the helpful action taken towards healing a sick patient was done by physicians whom only the rich could afford (Kenyon, 40). Even if a family was rich enough to afford a doctor, not all doctors practiced the same way. Each physician’s personal philosophy and education influenced the treatment they prescribed for different illnesses (Kenyon 40). Most medieval doctors held the Grecian belief in the four humors: sanguine, choler, phlegm, and melancholie (Kenyon 41). Any illness was the result of an imbalance of these humors. Below the physicians were the surgeons who did the dirty work (Kenyon 41).This included jobs like pulling teeth and bloodletting (Kenyon 41); and operating on hernias, cancer and gallstones (Kenyon 42). Those towns that were lucky enough to have hospitals did not use them as medical centers, rather they were more like the nursing homes and hospis care of today. They were places where the elderly could spend their last days “in peace and comfort” (Pounds 70).

Most of the lower classes were too poor to afford an educated physician, and so they relied upon the more practical medicine of women and elders (Kenyon 39). They used herbs, poultices, and massage to heal all ills. Usually this medicine did not help to treat anyone’s maladies. Medieval doctors had “no concept of pathogens” (Pounds 141). Illness was seen as divine retribution (Kenyon 39). Humanity’s sin was being punished by God (Pounds 58), and it was not unusual for the sick to go on pilgrimages to make peace with God. They believed that this true repentance would grant them recovery (Kenyon 39). Despite the deep belief in Christianity, medicine women and elders still used more pagan cures, such as incantations and spells, more than anything else (Kenyon 40).

Most of the lower classes were too poor to afford an educated physician, and so they relied upon the more practical medicine of women and elders (Kenyon 39). They used herbs, poultices, and massage to heal all ills. Usually this medicine did not help to treat anyone’s maladies. Medieval doctors had “no concept of pathogens” (Pounds 141). Illness was seen as divine retribution (Kenyon 39). Humanity’s sin was being punished by God (Pounds 58), and it was not unusual for the sick to go on pilgrimages to make peace with God. They believed that this true repentance would grant them recovery (Kenyon 39). Despite the deep belief in Christianity, medicine women and elders still used more pagan cures, such as incantations and spells, more than anything else (Kenyon 40).

FAMILY LIFE

The average lifespan of a medieval person was from 60 to 70 (Brooke 100). Some lived to be eighty years old or more (Brooke 100). The population was still in a steady declination. Most children did not survive the first year of life, and of those who did, very few made it beyond twenty (Brooke 99).

Childbirth and Early Life

Pregnant women were not considered endangered enough in the child-birthing process to actually require a physician (Kenyon 42). Instead they had midwives whose duty it was to try and make the birth go as smoothly as possible. Though they meant well, there was not much that could be done to ease the mother’s pain. What they did do was close off the birthing chamber, only women were allowed, and rub ointment on the mother’s belly which was supposed to alleviate some of the birthing pains. (Kenyon 42). An old superstition about closed things in the house prompted the opening of every single closed thing. It was believed that with everything open, even the knots untied, the birth would be easier for mother and baby (Kenyon 42). Women gave birth in a sitting stance or on a birthing chair. While in this position gravity could help birth the baby (Kenyon 42). After the baby was born it was washed, rubbed down with salt, its mouth cleaned out with honey, and then bound in a tight swaddling (Kenyon 42). If it looked like the child was not going to survive the midwife would quickly christen and baptize the baby. Kenyon 42). If it was the mother dying, then the midwife used a Caesarean Section to quickly free the baby (Kenyon 42).

If the baby was lucky enough to survive birth, it still had to fight for its life. One in three babies didn’t survive to the age of Five (frugoni 126). It was the custom to send for a wet nurse once the baby had been born because usually the mother did not have the ability to provide milk for all of her children who needed it (frugoni 126). Fertile women gave birth about once every eighteen months (Frugoni 127), and so usually there were at least two children who required milk from a mother who was sometimes malnourished to begin with. Sometimes the wet nurse’s foreign milk was fatal to the infant, but in other cases it was quite helpful with large families (Frugoni 126). Newborns and infants were kept in rocking cradles (rugoni 121) until they were old enough to begin walking. At that point they were placed in small walkers until they mastered balance (Frugoni 127). Soon after the child was old enough to play and run, they were apprenticed off into a trade, and a different household.

Education and Beyond

Urban children were apprenticed out to a trade between the ages of five and twelve (Kenyon 51), and signed onto for a seven year education (Kenyon 47). The education of male children went as far as their trade, unless they belonged to a wealthier family which could afford to send them to study at a university (Rice Jr. 45). Female children learned all of the “domestic arts,” that would help them run a household (Rice Jr. 45), as well as their trade. These domestic arts included spinning, embroidery, weaving, knitting, sewing, and cooking (Kenyon 147). Many families were illiterate and their children never learned to read or write (Frugoni 133). If they ever did learn reading and writing, there was a good chance that boys and girls would learn basic math as well (Frugoni 146).

Girls usually did not return home to live with their parents, unless it was for a short while until a marriage could be arranged (Kenyon 51). Unlike rural young men, urban young men did not marry until they had secured a place in the community with their trade (Pounds 55). Wealthier middle-class men did more than pursue a trade, they often had businesses as well, and were politically active (Rice Jr. 45) Their counterparts were just as busy, but considered second-class citizens none the less.

Girls usually did not return home to live with their parents, unless it was for a short while until a marriage could be arranged (Kenyon 51). Unlike rural young men, urban young men did not marry until they had secured a place in the community with their trade (Pounds 55). Wealthier middle-class men did more than pursue a trade, they often had businesses as well, and were politically active (Rice Jr. 45) Their counterparts were just as busy, but considered second-class citizens none the less.

A Woman’s Place

Medieval Woman -Urban middle class

In the early middle ages there was a shortage of women, and men had to pay a “bride price” to marry one (Kenyon 54). However around the eleventh century primogeniture inheritance (everything to one son) replaced consortial inheritance (Kenyon 55). Because of this, the supply of eligible men began to shrink. Soon there were more women looking for husbands, than husbands looking for wives (Kenyon 55). The value of a daughter dropped, and dowries began to rise. It cost a family to marry off their daughter Kenyon 55) ,and so they became even more unwanted. Women who could not find a husband became nuns, or burdens on their families (Kenyon 55). Medieval women were generally believed to be weak-willed and less able than men to resist sin (Kenyon 54). They spent their lives under the control of a man, whether husband or just a male relative (Kenyon 55). Still, it is not possible to exactly pinpoint the role of women, because of the diversity of relationships (Kenyon 54).There are records of female surgeons, midwives, warriors, leaders, eye specialists, journeywomen, and peddlers (Kenyon 55). Most women still managed to marry later in life and maintain some freedom with their husbands (Kenyon 54). Husbands often went away for long periods of time trading goods, which made it easier for women to live more freely (Kenyon 55).

It was very rare for siblings to grow up together or see each other very regularly (Kenyon 51). This does not mean that medieval families were not close or loving. In fact most children came home to visit their parents several times a year as they grew up, and well into adulthood (Kenyon 51). It is difficult to make any kind of judgment about how families behaved, because of all the mixed reports. Historians believe that it is safe to assume that there was a range of all kind of parenting, from extremely affectionate to unhealthy and violent environments (Kenyon 52).